By: Paul Hunting, Author Shakespeare’s Revelation

The drowning of Ophelia: its mystical symbolism revealed

“Nymph, in thy orisons, be all my sins remembered.” – Hamlet

Hidden in the symbolism and word-play of Shakespeare’s plays is the most important (forbidden) truth about who we really are and why we’re here on earth. In order to marvel at this subtext story, you may need to make the fundamental paradigm shift.

The key paradigm shift is to see the characters not as people in the real, historical, or fictional external world, but as characterizations of three pairs of archetypes of our primary internal states of consciousness. Having been a spiritual psychologist, theologian, and executive coach for over 30 years, I thought I was dreaming when I first realized that Shakespeare, to drive the plots of his plays, was using the exact same model of consciousness I have found invaluable to navigate my clients through the labyrinth of the ego into a more soul aware state.

The most confusing element of the subtext – and thus most intriguing – is the plethora of different symbols that refer to what Shakespeare ultimately calls ‘The Tempest’. The Tempest shows up like Alfred Hitchcock, in some guise, in all the plays. Often it’s so subtle it’s almost invisible (as in Measure for Measure).

At the anagogical level, the symbolic story Shakespeare always tells us is ‘How Adam and Eve lost the ‘Holy Grail’ and how Jesus Christ got it back’! ‘The Tempest’ turns out to be Shakespeare’s term for what has become mythologized as none other than ‘The Holy Grail’.

Hamlet is one of the most masterful disguises-and-thus-revelations of this never-before-realized analogy. As I said, if you suspend all disbelief and open your mind you may see this for yourself as I simply point out what the symbols say to me.

As you can see from the pictures, all these biblical and Shakespearean symbols seem to represent the one same thing, for convenience let’s just call it: ‘The Holy Grail’.

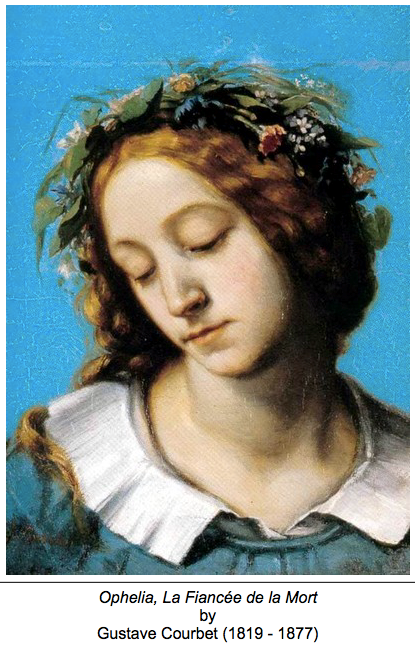

Ophelia’s role in Hamlet seems in part to represent the journey of Hamlet’s soul – independent of Hamlet as a mortal being. The key symbol used for Ophelia’s mystical travels is a variation of the term ‘the waters’.

The waters are first seen in Genesis 1: 2 (And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.) In multiple forms of water (seas, rivers, brooks, streams, rain, etc) the waters is a ubiquitous symbolic reference throughout the Bible and Shakespeare. (For a fuller explanation please read my book, Shakespeare’s Revelation.)

Using a ‘brook’ to represent ‘the waters’ goes back to the biblical story of David and Goliath. Symbolizing the power of ‘the Name of God’ to vanquish ‘evil’, it’s interesting that the boy-king David, holding a staff (another symbol for the name of God), took five smooth stones (again, more symbolic names of God) from a brook before defeating Goliath.

No coincidence that Ophelia appeared to drown falling from a willow growing ‘aslant a brook’. (Bear with me!)

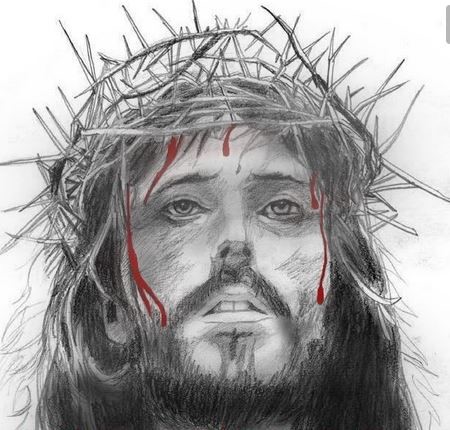

Combining these symbols with the images conjured by the poetry is all-important here. We have the image of a wronged-innocent being borne aloft and transported by a stream of water, adorned by (in particular) ‘coronet weeds’…and ‘long purples’. While she is ‘chanting old lauds’ (praises).

This, to me, evokes the images of the crown of thorns and the purple robe worn by Jesus at his trial and execution. Before you call the men in white coats, if you look, you’ll see elements of this motif also evident in many of the other plays, too. (Macbeth, for example, laments that: ‘upon my head they placed a fruitless crown and a barren scepter in my gripe’.)

In some of the ancient spiritual mystery schools, initiates chant ‘sacred tones’ to attune them to what’s sometimes called the Sound Current, the lifestream, that, it is said, draws the soul home to the Godhead – in the same way, it is the haunting music that draws Ferdinand to Miranda in The Tempest.

After all, in Twelfth Night (Epiphany), music is ‘the food of love’ and the principal character, Viola, is named after a musical instrument, and disguised as a boy called Cesario (King).

Before she meets her watery death Ophelia is heard raving ‘madly’ chanting:

How should I, your true love know

From another one?

By his cockle hat and staff

And his sandal shoon.

A cockle hat is worn by a pilgrim (one on the journey to God) and sandals are often associated with Jesus

Then up he rose, and donned his clothes,

Again, alluding to the resurrection of Jesus.

And here’s the wonder of Shakespeare’s layer upon layer of symbolism: while Ophelia is ‘drowning’ in the glassy stream Hamlet is simultaneously traveling upon the waters to England.

It is on this watery voyage that Hamlet foils the plan of Claudius (Satan archetype?) to have the two ‘Jews’, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern murder him. And what is a ‘rosen Crantz’?

A crown of roses/crown of thorns!

And there’s yet another layer of symbolism inherent here – if you can bear it:

One of the most persistent mythological motifs in the deepest drama is ‘symbolic resurrection’. Shakespeare uses is his through, say, Desdemona, Juliet, and Cordelia who momentarily revive (or seem to) before their final death. Banquo ‘resurrects’ as a ghost. And here it is again with Hamlet. In surviving his attempted murder, he effectively ‘resurrects’ and when we see his new, upbeat mood in the final act this is corroborated.

Staying with this theme, things get even more delicious. When Hamlet arrives home in Denmark, just before he gets to Elsinore, he comes upon a cemetery outside the city walls. A grave is being prepared for none other than his beloved Ophelia. She is being buried outside the city walls because it is presumed she committed suicide. Why? (Gertrude’s description of her reported death says she fell from an overhanging bough.)

Why indeed? Surely, this is Shakespeare’s device for introducing his clincher symbol. Ophelia has to be buried outside the city walls. What does Hamlet find in the grave being dug for her?

A skull

The most iconic scene in all of Shakespeare is no less than an allusion to where Jesus was crucified and buried, outside the city walls at Golgotha, ‘The Place of a Skull’!

And when they came unto a place called Golgotha, that is to say, a place of a skull…they crucified him.. Matthew 27:33

For a free eBook Contact: [email protected]

http://www.shakespearesrevelation.com

Paperback from Amazon: http://a.co/d/jgXcBWT

- Savage Land Book 1, Endangered Species - January 24, 2025

- Einstein’s Compass Five Star Book Review - October 13, 2024

- Book Club Mom’s Author Update: News from Grace Blair - February 18, 2024